iv. Empires Rise and Fall

The months wax, the years wane, empires rise and fall.

Everything changes, but not the lovers. They remained unchanging, each the lodestar by which the other steered. Through rich winter reds and crisp summer whites, they sipped from the cup.

They never grew up, they never grew old, they never got over the hill.

They just strolled and sipped, dancing in tandem, arm in arm, glorying in the wide vistas, at the shimmering lights, at the immaculate machinery of the City, at their own miraculous minds.

And Truelove whispered to her one night in a fog and a haze: “How did we get here?”

Shell’s eyes opened to the darkness: “Get where? Into bed? We-”

T: “No. Here. The garret. The City… I don’t remember…”

S: “Oh, my love. We’ve been here before. There’s no point.”

T: “No point in talking about it? Or no point in remembering?”

S: “Tru. What do you remember about your life? About me? Can you even picture the City outside? When did we meet? Where?”

“That’s just it,” he said. “When I try to remember anything, my mind just empties itself and winds up back here, in this room, with you.” Shell twisted in the sheets so she could better make out his silhouette.

“How awful,” said Shell, contorting herself to fit his shadow’s shape.

T: “It could be worse. Maybe its all a dream?”

S: “That would be a disappointing cliché. Anyway, we can’t even get to sleep, so it seems unlikely.”

T: “Well, you can’t. Maybe this is my dream?”

S: “Maybe.”

T: “Or maybe this is what a dream feels like from the inside. We are not the dreamers, but the dream-ees”

S: “Dream-ees. I like that. Anyway, it’s not a dream. It’s a memory. That’s what you said.”

T: “When did I say that?”

S: “I can’t remember…” Shell sighed, turning her head away from his and letting it sink into the pillow.

T: “I’d say forget it, but that’s all we ever seem to do.”

S: “Well. Now I just feel empty.”

T: “Maybe that means somebody is ready to fill you up again?”

“Who?”, asked Shell. “You?”

Silence.

S: “Maybe we should take some more?”

T: “Yeah. Okay.”

Truelove walked his fingers in the dark for two pills from the little pillbox by the bed. It was impossible to know what colour they were, but they each swallowed them without water or hesitation.

The clock stopped then, and they lay there, side by side, wide-eyed in the dark, wondering what would happen next.

xviii. The Edge

Shell picked up the ebonized pillbox and shook it. Silence.

“We’re out,” she declared.

“I know,” replied Truelove. He was attempting to shave in the sink without the aid of a mirror.

S: “And…?”

T: “I’m onto it.”

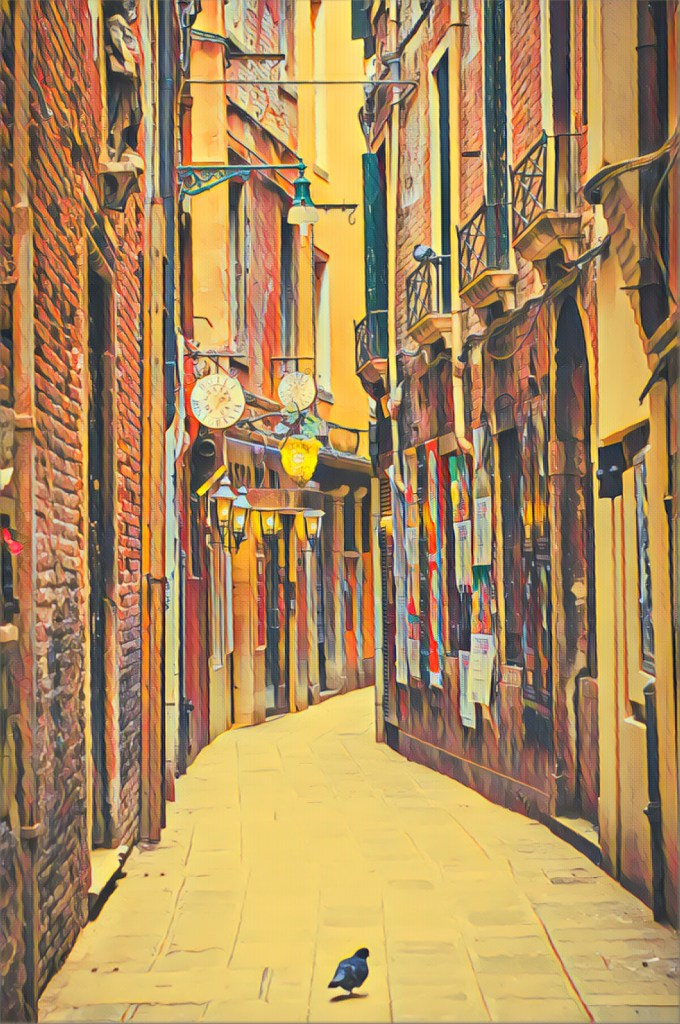

The Cross was not flat. The clutter of warehouse-filled streets between Darkthorne Avenue and the canal sloped down imperceptibly; but on the other side of Darkthorne the land rose steeply, and the main residential areas of the Cross were stretched up a terraced hillside, packed with tenements. Truelove and Shell’s building was here, on Montague Street, about halfway up a hill steep enough to make riding a bicycle impractical. Narrow lanes ran up and down in a regular grid, superimposed on the hillside. The one exception to this artificial uniformity was the snaking route of Peacock Parade, which sliced through the grid, creating odd angles at the intersections. The tenemented hillside of the Cross was alive with people at all hours, from all places, all times, each of them rich with their own stories, their own lives. Most had very little but their lives and this place. The Cross was a refuge for the lost, though none of the lost realised this.

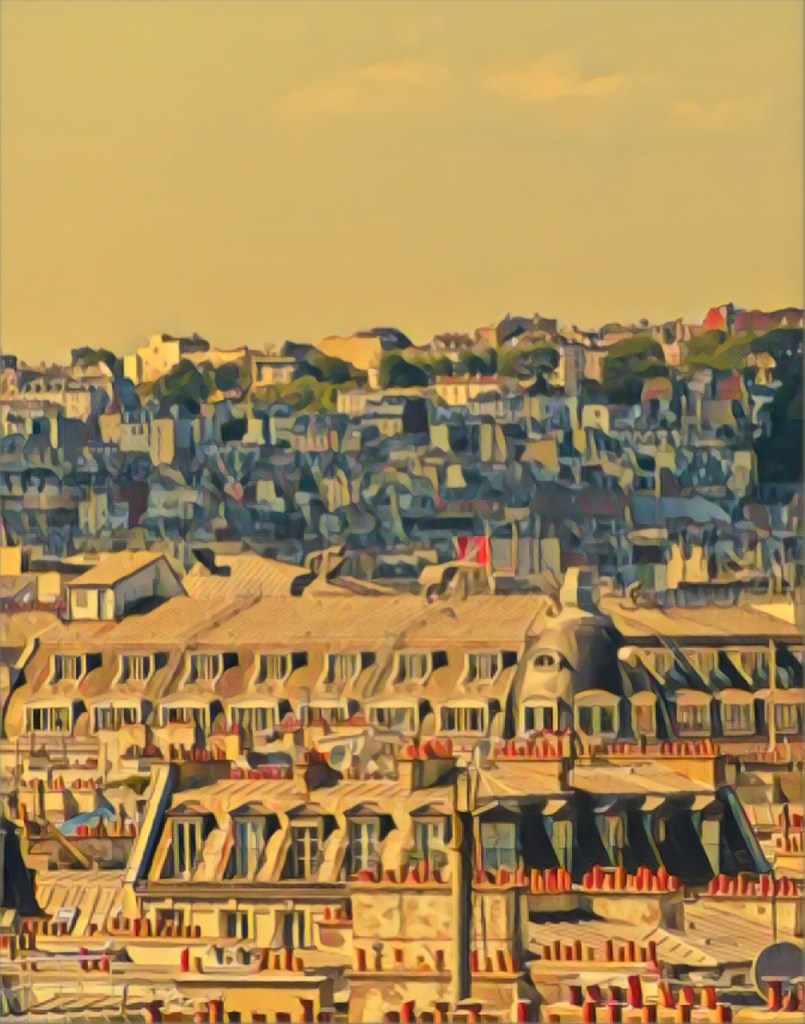

At the top of this slanting maze of tenements, the land fell away sharply towards the river on the other side, a cliff known simply as The Edge. Tenements had been built to the very top, and in recent memory The Edge had crumbled and collapsed, and whole buildings and their occupants had tumbled to their deaths. Most of the remaining apartment buildings at the very top had been abandoned. Some had half-collapsed, their rooms exposed by fallen walls like honeycomb; others teetered over the cliff itself, awaiting the inevitable. In the Cross ‘living on the Edge’ had a very particular meaning.

The terrace of tenements all faced the turgid canal below, with the industrial wasteland of Petrarch on the far bank. The sudden precipice of The Edge at the top of the hill meant that The Cross had effectively turned its back on the City’s great river beyond. Below the cliffs of the Edge, the banks along this particular stretch of the river, were wild and wooded, dotted here and there with the rubble and ruins of collapsed buildings. This place was known locally as the Backwoods, but the people of the Cross had no particular cause to go there; it was merely what you fell into if you went over the Edge. It was a lost place, even for the lost.

Truelove climbed the narrow laneway up the hill and made his way to the Edge.

The man he was seeking out was a callow, wax-skinned youth by the name of Frame. Frame was the intermediary between himself, a petty dealer, and his enigmatic supplier. Everything went through Frame, and Frame lived on the Edge.

Truelove and Shell didn’t know him well. Frame was younger than both of them, but his manner was mature, serious. Sometimes they saw him in one of the cafés, his sharp features furrowed over a book (never fiction) or writing frantic notes in a neatly trimmed ledger. But they never saw him in the cabaret or carousing in a bar. They never saw him with his guard down. Frame, in spite of his youth, was composed.

He found the tenement where Frame lived on his own; that is to say, the entire six-storey building – or what was left of it – was Frame’s home, and his alone. Apparently, according to an account Truelove may or may not have dreamt up himself, Frame had inherited an apartment from an uncle who had died when that very same apartment had collapsed over the Edge into the Backwoods below. Only half of this late uncle’s apartment remained attached to the building, which was now riven in two. Indeed, all the apartments along the cliff-side – or what remained of them – were now open to the elements. The other residents had promptly abandoned the doomed building, but Frame had calmly claimed his inheritance, even if it was now just a narrow ledge hanging over the edge of a cliff. His legal right to this precipitous perch was undisputed and, owing to circumstance and the City’s arcane squatting laws, he now had possession of the entire remaining half of the building.

Truelove found Frame easily enough, eating his lunch on the ground floor, in what was once a café.

“Hello, Frame,” said Truelove.

“Truelove,” replied Frame looking up from his meal. “Like clockwork.”

T: “Are you winding me up?”

F: “No.” Truelove suspected Frame was irritated by anything frivolous, which is why he always tried to be.

T: “Are we all set?”

Frame regarded him coolly: “There are certain details… certain arrangements to be taken care of.”

T: “Okay. Like what?”

Frame smiled: “He wants you to go to him in person this time. You and… your… wife? Lover? Whatever she is to you, your…”

T: “Shell?”

F: “Yes. Your shell.”

Truelove could have sworn he saw a fine rain of powder fall from the ceiling, as imperceptible cracks imperceptibly widened.